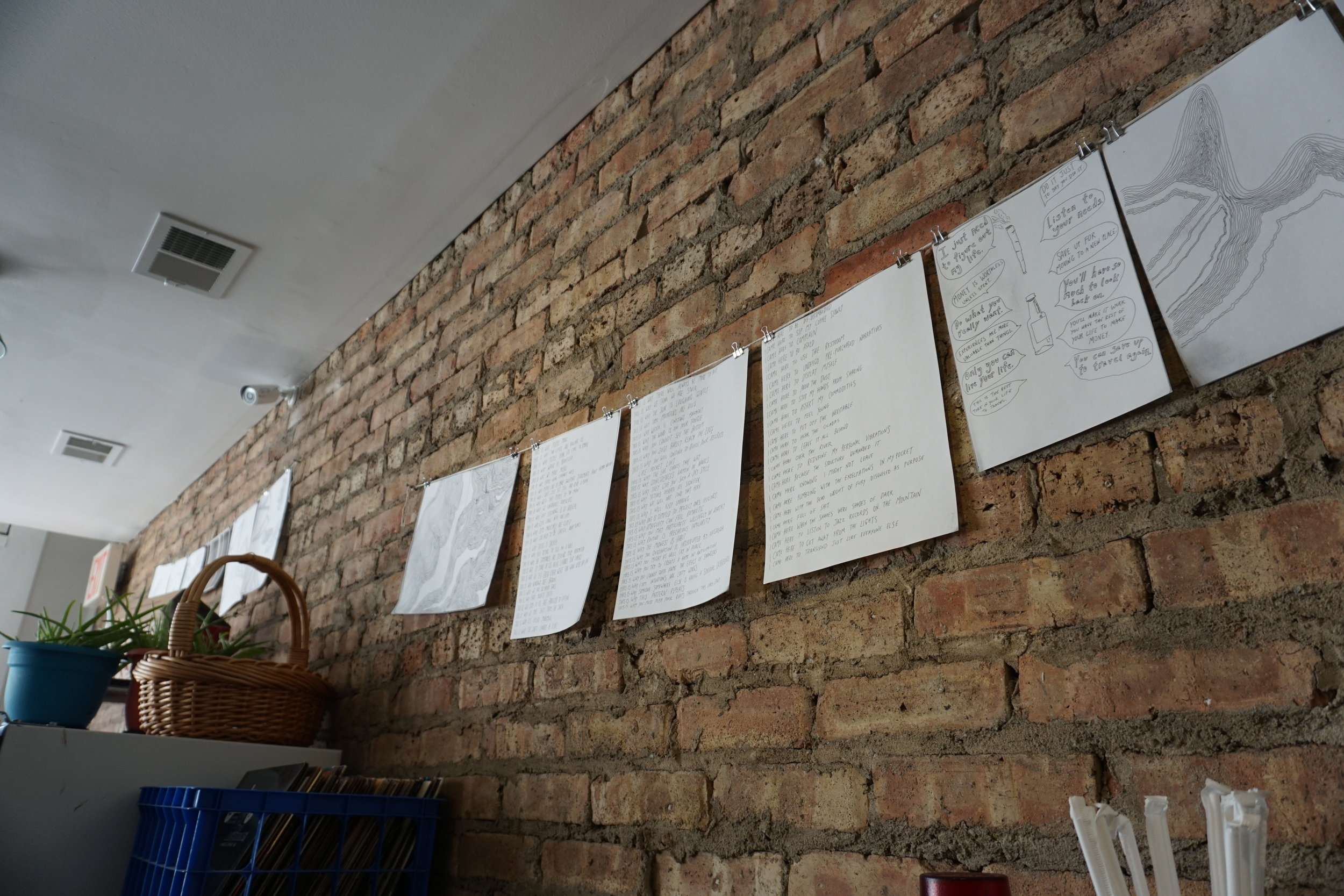

I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to display my artwork at Archie’s Cafe in Chicago from Jan - Feb 2019. This was my artist statement I read at the art opening for my show, Destination is interrupted by nostalgia, on Jan 12, 2019.

The Indian writer Amitov Ghosh, in The Great Derangement, wonders why climate change, arguably the most important challenge facing our world, is not depicted more in our culture, particularly in fiction. When future generations in a “substantially altered world,” look back at this relatively more stable time for expressions of our plight, and find very little, they might think of us as deranged. How could we not broach this unprecedented, all-encompassing reality?

While I want to leave room for interpretation, I do want to offer this context: my work is about climate change in the way that perhaps (I want) all work approaching relationships to “nature” could be said to be about climate change -- or all work created during this time has some relationship to climate change, even if it has no relationship. Ultimately I hope my work is able to ask particular questions about climate change, and create space for more questions to be asked.

Though my work is not fiction, I do not pretend photography is objective. The “nature” that so draws me is one kind of fiction, as it relies on a messy, unreliable dichotomy between nature and culture. How are humans already part of nature, and how might we be actively participating in our own alienation? How ought we define ourselves, being increasingly unable to ignore the “urgent proximity of nonhuman presences”, as Ghosh puts it?

Perhaps I am drawn to photography because of its seeming concreteness amid all this change. Though I hardly edit my photographs, there were many choices made in terms of framing, lighting, what to include or exclude. In this way, I too am participating in the commodification of nature, perpetuating the allure of a lifeforce that is so much more complicated than can be depicted here. In this way, I hope the images are as much about the loss of places as they are about the revealing and challenging these alienating ideas about nature.

While we have some visual language for climate change – melting glaciers, disasters, the ever fragile polar bear – we need new understandings for a mourning on this scale.

Climate change is about more than the drastic altering of our planet's climate due to releasing large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere due to industrial developments. That is the basic definition of climate change – but within that is a question, is so many questions, is a demand. Our mis/understanding of loss leaves many with a vibrating, underlying anxiety, grief and dread we can't always name. The real task may be to eke out the emotional landscapes, to insist on facing and feeling this. Our public reckoning remains to be seen, felt, heard, and lived.

Climate change is not an event, but a process, an accumulation of history that is determining the future. It is right now and it is also the cultural, socioeconomic, political, spiritual and intellectual forces that led to its consequences, that allowed the release of carbon to continue, and that remain functioning in denial.

Climate change forces us to confront how we orient ourselves to our surroundings, human and non-human. It reveals what forms we create, ignore, take for granted, and feel attached to. It is about our own bodies being bodies of water, and how we pollute both. It is about how to make a home in the increasingly unfamiliar. It is about human lifespans, and it is also about the lifespan of a rock, which is to say, sweeping insignificance.

And visual language can only cover so much ground. Feeling the need for new words to describe this particular feeling, the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term solastagia: “the pain experienced when there is recognition that the place where one resides and that one loves is under immediate assault (physical desolation). It is manifest in an attack on one’s sense of place, in the erosion of the sense of belonging (identity) to a particular place and a feeling of distress (psychological desolation) about its transformation.”

- - -

Many of my photographs come from my travels, some with strong memories attached. I heard once that when we recall memories, our brain must recreate the story we tell ourselves, so that in each retelling, our memories are altered slightly each time. We end up losing memory even as we try to keep it alive.

The carbon stored deep under the surface of the earth is another memory, too – one that, in extracting and releasing it, we have granted unknowable contortions. It is a memory that has killed us and will continue to, a memory we ought to have left alone. Now we see it, spilling out across our oceans and continents and in our atmospheres, spilling and condensing timescales and tenses in ways we are still trying to measure, record, communicate.

As landscapes shift around us, in their ebbs and flows and unexpected surges, we become travelers even in familiar places. Some of us are tempted to remember nature as stable, balanced, conservable, preservable: but what version of an ecosystem is worth keeping? What is the relationship between aesthetics and functionality?

My drawings, as various studies of repetition, hopefully speak to this memory problem too. Because we cannot go on as we have before, we must go on as we never have. As our possible futures take shape, and certain projections of sea level rise or mass extinction become cemented, not only do we shift, but the world around us does too. What ideas, histories, harms will be repeated, and which ones will we let go of?

Nature was never really stable, balanced, conservable, preservable – and this time, we have no choice but to come to terms with our intimate interdependence. What we want to call “nature” becomes a subject, impermanent. We learn new types of object permanence: when winter has no snow, autumn has a heat wave, and our seasons seem to falter, how do we know where we are? How do we create maps of places, physical or emotional, that we know will change?

- - -

Much of my life has existed in the “I will have done” tense. Because of my various privileges and life circumstances, I was handed an implicit and explicit map: by the time I die, I will have gone to college, gotten a good job, settled down with kids, a car, a TV, and so on. This is not the life course that most of the world follows, and I recognize that my life will not be nearly as altered as it will be for other parts of the world, such as the Global South, people of color, poor people, and others on the frontlines of climate chaos.

Besides my rejection of this American dream, I can't help but feel a peculiar sense of loss and anxiety knowing my life will look very different from any generation before me. When I imagine myself in future destinations, both in time and place, it already feels interrupted, shattered. The uncertainty of my individual future feels exacerbated by the collective uncertainty of my and future generations.

Facing this uncharted territory after graduating in May 2017, I decided to embark on a long walk. I would embody the uncertainty of my own path by creating a literal path. Like a lot of white Americans, my European ancestry comprises a hazy mix of countries that I don't need to understand to survive in the world. Whiteness in many ways feels like a crisis of place, as it paves over cultures and histories, becomes so visible it is invisible, turns spaces with a sense of place into commodified sites of repeatable, capitalist transaction: non-spaces. Walking forces me to slow down and actually, physically and emotionally, be in one place.

Last October, I walked from Paris, France to Bonn, Germany on a personal pilgrimage to the United Nations climate talks, known as COP23. These two points created a symbolic as well as representative path through my own family history, as well as a global history. The distance between Paris and Bonn is similar to the distance between Chicago and Ann Arbor, Michigan, my place of birth and where I grew up, respectively. My father's family is mostly German, and France was an important place of personal growth for me, as my family was lucky enough to spend a year there to support my father's work as a particle physicist with a European laboratory, CERN.

This walk was another way to map out what my world was made of, knowing the planet would continue to change rapidly in ways we've never seen. It was a gift of slowness to myself, and to the world.

- - -

Ours is a generation defined by precarity and uncertainty, a permeating anticipation of loss, but not knowing completely of what. There is no away space, in time or place: we will all have moments when climate change feels personal, when our disorientation becomes the new normal.

Perhaps my photographs are a kind of topography of loss, as much as a record of abundance and presence, documenting what I hope not to lose to climate change, but that has already been changing.

There will be no singularity of apocalypse. There is still slowness. There are still roadtrips, and we can still make maps.